International solidarity, so affirming as a slogan, can in reality be selective and polarizing. It elicits strong feelings, stark denunciations, passionate finger-pointing, and unlikely alliances. But it might also become a proxy for various political interests quite remote from those with whom solidarity is claimed.

That is exactly what happened when the war started in Ukraine. In just a moment the affairs of our poor peripheral country became a matter of nearly global debate. We’ve seen it all: from big gestures and loud applause to strongly worded statements and even countries opening their borders. However, it soon became apparent that most of this attention was fueled by the onlookers’ own domestic agendas.

Solidarity as a proxy

From the very beginning, the Western liberals were among Ukraine’s strongest backers. Sadly enough, this solidarity tended to be at somebody else’s expense. First, Ukrainian refugees were thrown at the already stretched and underfunded welfare systems, sometimes infused by previously denied funds or, more likely, tasked with re-prioritization. Moreover, not infrequently the need to support Ukraine was used to justify austerity at home. Even intensification of the munitions handling, as in the UK, went hand in hand with blackmailing the unions. A choice of policies was destined to eventually undermine the very solidarity they were motivated by.

Besides, the Russian invasion became a battering ram to bypass proper deliberation and push through unprecedented military consolidation, award multi-billion contracts for the arms industry, and shift spending focus away from the climate goals. Meanwhile, the supplies to Ukraine have been often delayed, its grain exports were blocked for months, and the extent of commitments depended on personalities like Trump and Orban. And nonetheless, the Russian gas, oil, and uranium kept flowing in, and Western high-tech production continued to find its way to Russia.

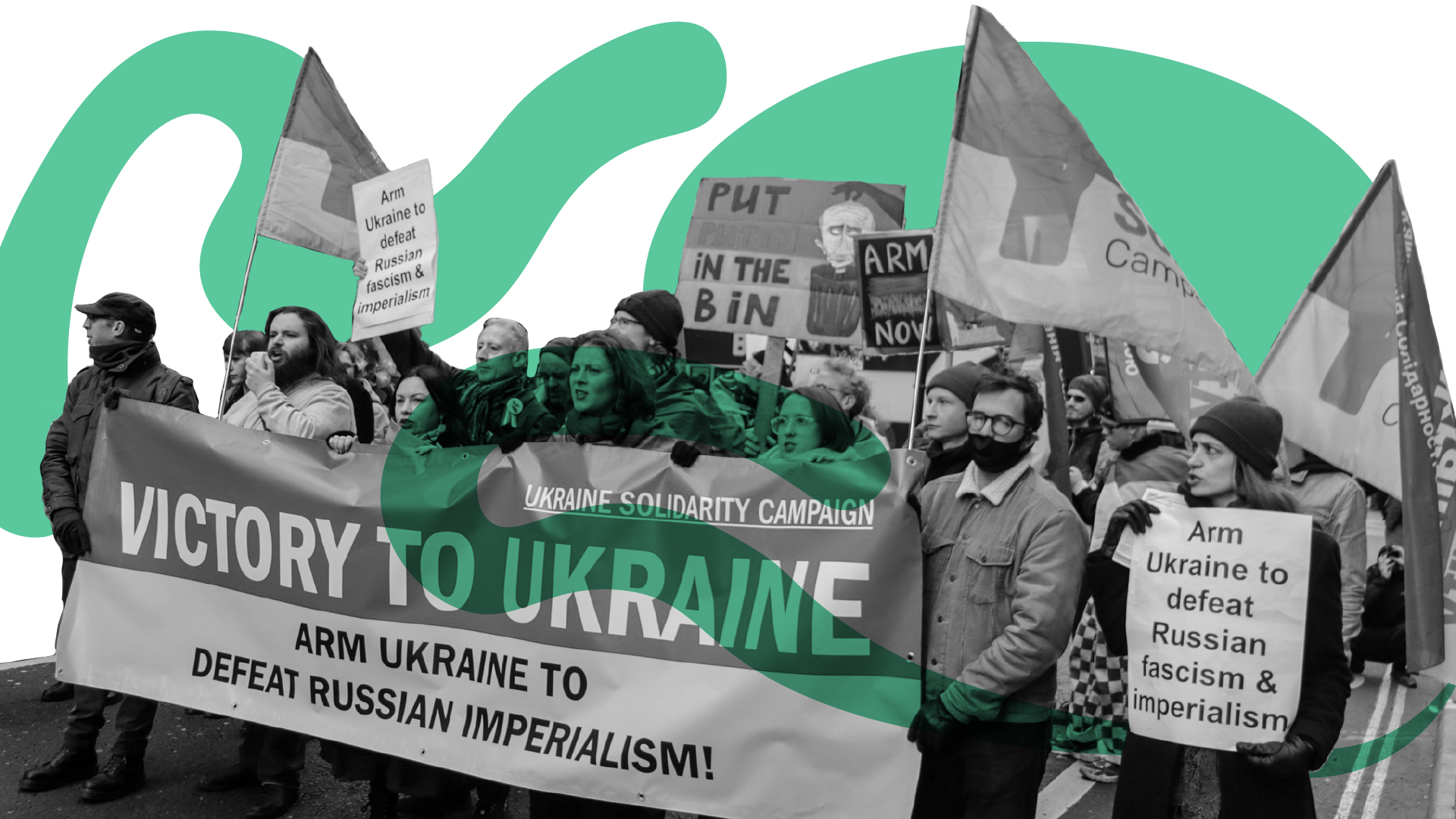

The left, on the other hand, despite years of championing internationalism, faced an existential challenge to their long-established worldview and priorities. Too many, entrapped by their past traumas or devoted to once proclaimed virtues, were not able to look beyond domestic political struggles and stale cold war positions. To some, open and consistent support of Ukraine became straightforwardly associated with bourgeois politics and nothing more than another piece of evidence of its double standards. In the end, ‘the main enemy is at home,’ and the appointed friend of your enemy is certainly not your friend. Therefore, for the last two years, the left has mostly oscillated between half-hearted support and awkward indifference.

With this in mind, it is no wonder that discussions quickly took the form of a scholastic exercise, completely devoid of ‘the concrete analysis of the concrete situation’. “This is all a patriarchal endeavour, a proxy war provoked, of course, by the ultimate evil, the West, a business of Ukraine’s capitalist government.” Clichés like these became widely used to assert one’s true radical identity or high moral standing. The messy reality would only complicate things unnecessarily. After all, isn’t it our sacred duty to be the voice of peace? Why don’t the workers in Ukraine and Russia just unite and overthrow their rulers?

That is how, regardless of political views, Ukrainians end up locked in the camp with people whose benevolence, at best, extends to their class cronies and whose every other step pits the rest against each other. Even when you are not exactly in the position to choose, your natural allies take this as a convenient excuse to distance themselves further and, with relief, renew the barricades guarding their comfort zone.

Solidarity for itself

In the ideal world, it wouldn’t be hard for anyone honestly concerned about the people to start with having a closer look at them. Who are these “bourgeois classes” arranging Ukraine demonstrations, as Kajsa Ekis Ekman calls us? Are they not immigrant workers who lost their lives at the construction site in Sundbyberg? Are they not humiliated, overworked, and cheated farmworkers of Skåne? Are they not exhausted cleaners in greater Stockholm spending hours in unpaid commutes, or the desperate women forced to sell sex to provide for their families?

What does it take to consider who will be ”fighting with the shovels” if the ammunition runs out, as Ukraine’s Foreign Minister pledged? Will they really be rich men? Or rather one of the 45 thousand women or ten thousand railroad workers in the army? Are there any doubts about whose household or livelihood will be exposed when the air defence capacity is reached? Who will gain more from a ‘revolutionary defeatism’, the semi-alive and demobilized labor movement, the non-existent mass-membership left parties, or the organized right wing?

A cure to pointless virtue-signalling is understanding that words have consequences, especially for those under the bullets or at the forefront of exploitation. It may look all the same for the performative radicals behind the screen, but there is a difference for those who risk being at the mercy of the Russian regime: political activists, trade unionists, and journalists, whom the Kremlin evidently doesn’t spare. There is a difference for feminists and the queer community against whom Putin declared his crusade. There is a difference for those who cannot flee, and there is a difference for those who are forced to, nonetheless. Not everyone can afford the benefit of abstract reasoning.

Obviously, the appeal to solidarity should not equal a prohibition against criticizing the elites if they dress their policies with the right colors. But it should neither suggest dismissing their every action outright as witting and shallow hypocrisy. Take them at their word and expose any inconsistency without backstabbing the people on the ground. What does every single proposal, package or policy measure primarily contribute to? Does it keep things as they are, strengthen protections or power of the working class, weaken them or perhaps mostly enrich the policy makers’ sponsors? Even selfish and insincere gestures can be useful if someone demands accountability.

Of course, internationalism has nothing to do with an arrogant requirement to renounce any doubts or forget your own interests. The same circumstances, which are used to justify scrapping a public holiday or to pump up the price of Wallenberg shares, can be reasons to demand a tax raise for billionaires or socialization of the weapons industry. Comrades should be able to discuss challenges openly and seek solutions together.

Beyond Westplaining

Having said that, Ukrainians can equally be self-centered, naive, traumatized, or hateful. We’re adamant about our bright European future, we put unreasonable demands on those in the occupied territories, we’re quick to call others Putin’s slaves, and we believe that the only good Russian is a dead Russian. But doesn’t it make the point that the dialogue is vital?

Genuine internationalism is rooted in backing ordinary people, acknowledging one’s concerns and down-to-earth agendas, looking beyond the stereotypes, and building up on what we have in common. This is not because of a moral duty or a bad conscience, but out of compassion for and solidarity with those like us. When the right-wing wave is coming, wage earners around the world have no one else to rely on but each other.